Creating a relevant suite of test devices

“What does having a relevant pool of equipment mean when I have to test applications? If I’d like to create a test set of mobile devices from scratch, where should I begin? My testing pool hasn’t been updated for a long time; what criteria should I check to update it?”

In this blog post, we will offer basic answers to these essential questions. More particularly, this blog post will focus on the criteria to keep in mind while creating a pool of Android test mobile devices.

Indeed, finding a relevant testing set of Apple devices is easier, for several reasons.

For starters, the adoption rate of new versions of iOS is impressive: with the release of iOS7 in France, more than 50% of iPhones users installed it within a week (source). Now, 90% of Apple devices in the world are currently on iOS7 (source).

Also, new iOS versions tend to be compatible with most Apple devices. iOS 8 is a good example as it will be released on every Apple smartphone and tablet with the exception of iPhone 4/3GS/3G and iPad 1 (source).

More generally, Apple’s vertical integration strategy makes life easier for developers. The fact that Apple designs its products from the CPU to the operating system enables developers to create mobile applications in a monolithic environment: the list of different devices is short, and these devices have the same operating system and also a similar hardware architecture.

Consequently, if you are developing applications on iOS, there is no need to test them on every possible device. Testing them on each of the four screen sizes (iPhone 3x/4x, 5x, iPad, and iPad Mini) is enough. Just don’t forget to test them on iOS 6, to not forget this last 10% of users.

Conversely, Google has opted for a more horizontal strategy, focusing on the development of Android and applications / digital services. Therefore, Google gives device manufacturers free rein for designing smartphones and tablets that will be running on Android. The consequence is a significant fragmentation of the Android platform, with a host of entirely different devices (11868 different Android devices have been seen last year - source) running on several scattered versions of Android OS. However, Google has made a platform that gives a pretty good level of abstraction for developers, avoiding case-by-case testing. But in theory, to have certainty that an app work on all devices, you would have to test it on every single one! Obviously, this is impossible. But don’t panic: this article will help you build your pool of equipment in a way that enables you to guarantee to most users that your app is actually working.

What screen size and density should the devices on which I test have?

The first choice you have to make when it comes to get new mobile devices is about display features.

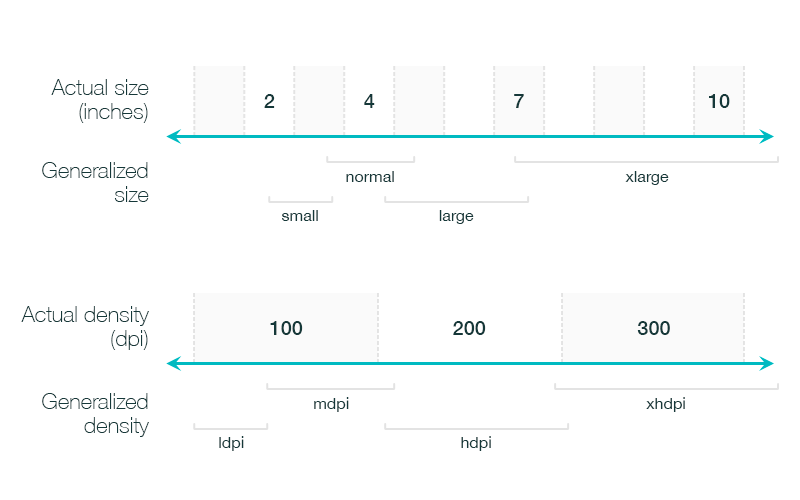

If you’re starting your testing set from scratch, it could be interesting to check out the screen sizes and density distribution of Android devices across the world (Google source). With those figures in mind, you will be able to create a testing pool that represents quite well the distribution of Android devices among the population. Then, by testing your apps on the most common devices’ displays, you will get the certainty of satisfying most of your users. Check out how these display categories are made with this little schema.*

If you just want to update your group of test devices, try to keep this in mind: a large number of Android users don’t have high-range devices. You don’t have to necessarily modernize your testing pool . Take actions to make sure that your apps are also working on small screen and low-resolution devices. Try to have at least one device of each size type: small, normal, large and xlarge. About density, widespread screen types nowadays are mdpi, hdpi, xhdpi and xxhdpi. Again, you should try to have one of each type and if possible, have various devices that mix different densities and screen sizes.

How powerful should my testing pool’s devices be?

Let’s keep talking about hardware technical specifications, and more particularly about how powerful your devices should be. This means how fast and efficient your devices’ SoC (System on a Chip, which includes device’s CPU and GPU) should be. Again, diversification is the word.

Having only powerful smartphones equipped with bleeding-edge SoC would be a huge mistake. Actually, you would be better off testing your apps on Android devices with average or low computing power. This way, when your apps are doing well on these devices, you become certain that you’re satisfying the average user of your apps and then that your apps will undoubtedly work well on faster devices.

No matter if your intent is to build a new set of equipment or just to update it, the main idea is always the same: be sure to have devices from all technical ranges.

Do I have to care about the OS tweaks and modifications added by manufacturers on Android phones?

You definitely have to. These modifications (including changes in the UI called skins and sometimes deeper changes in the OS) that smartphone manufacturers preinstall on top of the Android OS may change how your app works. Depending on the manufacturer and the way Android was modified on this phone, layout bugs may appear.

For instance, some OEMs install their own browser (running on a unique architecture). The consequences for developers are problematic: a single website will appear differently on each device with the tweak, and also, on each OS version.

Nevertheless, Google makes great efforts against fragmentation (source). Recently, device manufacturers have been forced to respect a few rules with their tweaks and skins. If they choose to not respect these rules, they automatically loose the ability to use Google services, such as Google Maps. For instance, manufacturers are compelled to install Google as search engine by default on their devices’ browsers or to preinstall ten of Google’s apps. Thanks to that, Google has managed to limit fragmentation among Android’s modifications.

To avoid bad surprises, be aware of the OEM’s modifications installed on the devices your app will be running.

Getting only devices running on stock Android UI to test your apps would be a bad solution: an app working perfectly well on stock Android won’t necessarily work as well with OEM modifications. Naturally, the best practice when it comes to testing your apps is to do it on the common skins: Samsung’s Touchwiz, HTC Sense, Sony Xperia’s UIs or LG Optimus UI. Again, you won’t be able to test your apps on every single OEM skin. By testing them on the four previously quoted skins along with stock Android, you’ll be sure to cover most users.

And what about the Android versions on my devices?

Now that we’ve talked about UIs, let’s take a deeper look into the OS particularities.

Google gives us interesting figures about the Android versions distribution across the world (Google source). If you’re just about to begin to build your testing pool, it might be interesting to get a pool following the global repartition in terms of OS versions. As you can see, the most widespread version of the Android OS is Jelly Bean (4.1-4.3). Thus, it is necessary to be certain that your app is working on at least these versions. After, you can diversify your testing pool by getting devices running on Ice Cream Sandwich (4.0) or KitKat (4.4) and then on older and more particular versions like Gingerbread (2.3.x), which represent only 14% of the global distribution in July 2014 (Google source). Nevertheless, experience indicates that usually, more problems come from the tweaks added by manufacturers than from the differences between OS versions.

Eventually, the main idea to keep in mind about OS and skin choices is that you should diversify manufacturers’ presence in your pool before diversifying OS versions.

Anything else I should know before I start to create/update my testing pool?

Before you begin to think about your pool of devices, ask yourself how exactly you are going to use this testing pool: what kind of apps are you going to develop? What users are you targeting? “Geek” users equipped with brand new high-range Android smartphones? Or average users who may have outdated low-range devices? Furthermore, be aware of the hardware features your app is going to need: sometimes these features are missing, even on high-range smartphones. Take a look at the issue Game Oven, a company editing mobile video games, had to face with its game Bounden. To work properly this game really needed a gyroscope, which is a common piece of hardware in current smartphones. Nevertheless they discovered that their game didn’t work properly on many Android devices as some of them didn’t have a gyroscope or had a very bad one…

You should also obtain information about the market you want to target, as its features can have a direct impact when creating a set of test devices. For example, Apple is the top manufacturer in the US, Xiaomi leads in China, and Micromax prevails in India. It’s important to target your tests and not shoot for the global market.

In a nutshell, try to keep these points in mind:

- Almost 80% of smartphone users have Android devices, but only a minority have fresh high-range phones: stubborn modernization won’t be as efficient as you might think.

- Android is a very fragmented platform, but you can increase your chances to satisfy the maximum number of users by diversifying your testing pool in terms of hardware, skins, and OS versions.

- Always adapt this advice accordingly to the specificity of the mobile application you’re developing.

We're hiring!

We're looking for bright people. Want to be part of the mobile revolution?

Open positions